You reached this page through the archive. Click here to return to the archive.

Note: This article is over a year old and information contained in it may no longer be accurate. Please use the contact information in the lower-left corner to verify any information in this article.

At 105, oldest Ole tells it like it was

April 13, 2011

Just a few months after Isaac Enderson graduated from St. Olaf College, the stock market crashed and a deep financial crisis gripped the nation's economy.

|

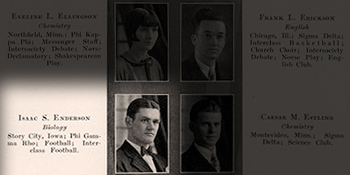

| Isaac Enderson '29 has a photo of the entire 1928 St. Olaf student body hanging in his room at St. Luke's Lutheran Care Center in Blue Earth, Minnesota, where he also keeps his letter sweater (which he's wearing in the 1928 photo) on display. |

Enderson knew that a little ingenuity — and a lot of hard work — could go a long way, so he put the entrepreneurial skills he'd developed as a student to work and built a successful career in the hardware business.

While Enderson's story is one that many recent graduates can relate to, he actually entered the job market more than eight decades ago. A 1929 St. Olaf graduate who just celebrated his 105th birthday April 10, Enderson tops the list of the college's oldest living alumni. And while he jokingly refers to himself as "a prehistoric animal," he's in remarkably good health and can still recall with acute detail what life was like on the Hill in the early 20th century.

An entrepreneur from the start

A native of Story City, Iowa, Enderson arrived on campus in the fall of 1925. Pursuing a college education made him an anomaly in a time when few farm kids made it past the fifth or sixth grade and fewer still graduated from high school and went on to college. Yet Enderson had decided that he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his older brother Jake and become a minister. His parents were Norwegian immigrants, so there was no question that to pursue that goal, he would attend St. Olaf.

But school was expensive, and Enderson had to find a way to pay for it himself. Luckily, he attended college in the days when St. Olaf required all men to wear neckties and sliced bread had yet to be invented. An entrepreneur at heart, he took advantage of both of those things to help pay the $72 per semester tuition.

He started by going door-to-door in the dorms and selling neckties to other students. He was good at it, he says, and he knew a lot of guys thanks to his role on the college's football team. The only problem was that he had just one box of samples, and almost everyone on campus chose the same tie. When the orders arrived, a sizable portion of the campus population stepped out wearing the same tie. And Enderson knew he had better find something else to sell.

|

| Isaac Enderson '29 (center, in black suit) and fellow classmates in a 1928 photo of the entire St. Olaf student body on the lawn outside Holland Hall. |

He tried selling socks, which was a flop, but then found that bread knives were a hot commodity. Enderson drove all over the countryside surrounding Northfield and sold Burns Bread Knives door-to-door for $1.10 a piece. His work netted him more than just tuition money. At one home he was struck by one of the owners' daughters and asked her on a date. That woman, Hazel Omundson, later became his wife.

Life on the Hill

Despite his natural talent when it came to selling things, Enderson arrived at St. Olaf with the intention of becoming a minister. His brother was already a student on the Hill planning to attend seminary, and they roomed together in Ytterboe Hall his first year on campus. But the younger Enderson's plans changed when he became familiar with some "PKs" (pastor's kids) at St. Olaf who also planned to join the ministry. "They were regular rounders as far as I was concerned, and I thought if that was what it consisted of, I didn't want anything of it," Enderson says with a smile.

So Enderson, whose mother was a skilled midwife, decided to major in biology and pursue a career as a doctor. That plan was derailed when tragedy struck his family in the deaths of his father, sister, and her two children within three weeks of each other. Enderson had to return home to help his family through that difficult period, and he fell too far behind on his studies to pursue medical school. He decided he would continue with his major and pursue a certificate to teach biology.

|

| The 1928 St. Olaf football team during its contest against Concordia University. The 1929 Viking yearbook notes that veteran center Isaac Enderson '29 "had good competition for the position, but his passing, accuracy, and headwork made him hard to beat." |

Football and free time

In addition to his studies, Enderson played center for the St. Olaf football team. The camaraderie between players and the support of the local community made playing on the team one of his favorite campus experiences. Legendary St. Olaf football coach Ade Christenson '22 had coached in Story City before returning to the Hill in 1927 to lead the Oles, so Enderson had the opportunity to play for him in both high school and college.

During Enderson's time as a football player, the team traveled to games in cars borrowed from community members. He remembers that a long caravan of cars would make its way to games held all over the area, from Gustavus Adolphus College to Luther College to Concordia University. And that wasn't the only thing that made the experience of playing football a little different back then. When Enderson was playing, the team wore leather helmets with felt padding.

"There wasn't much support if you got conked pretty hard," he says. "Of course, that was part of the game; it was a rough game, and every game you'd get bummed up something terrible. We played on Saturdays, and sometimes on Sundays you didn't know whether you should get out of bed or not."

|

| Isaac Enderson in the 1929 Viking yearbook. |

Enderson and his brother — who did, indeed, become a minister — eventually moved from Ytterboe to live in a private boarding house off campus. Yet they still found themselves in campus residence halls on a regular basis. Both of the Endersons earned some extra money by waiting tables at the dining hall of the Old Ytterboe Boarding Club and working in the cafeteria in Hilleboe Hall.

Between work and football, Enderson somehow still managed to find time to socialize. Even though dancing was banned on campus at the time — considered the "work of the devil" — he joined other students in sneaking down to Faribault on the weekends to attend dances.

After St. Olaf

Although he had intended to become a teacher upon graduation, Enderson changed his plans after a representative from the Gambles Hardware Store chain came to campus to recruit employees. He took a job with the company, and within a year became a manager. After more than a dozen years with Gambles, he had saved enough to open his own hardware store. "I figured if I could be that successful with them, I could do it for myself," he says.

When Enderson's brother-in-law returned from serving in World War II, the two opened a shop in Blue Earth, Minnesota. It housed a hardware store in the front of the building and a heating, ventilating, and air conditioning business in the back. They employed 10 people, and Enderson involved all three of his daughters in the business. One of his daughters, he notes with pride, learned to do repair work better than almost anyone in the business. He officially retired from his business at age 85, but continued to do contract work for years after that.

While Enderson can't remember the last time he was on campus, he says being at St. Olaf built his character and set his standards for living. As someone who has seen more than a century of economic fluctuation, Enderson's advice for current students is simple. "Follow instructions and be outgoing," he says. "Learn to apply yourself to the best of your knowledge, and don't be afraid to try something new."

That philosophy has worked well for Enderson, who lived on his own until moving into St. Luke's Lutheran Care Center in Blue Earth just last year. So what's the secret for his longevity? "I picked out parents with good genes," he jokes. "And I tried to make the most out of every situation."