You reached this page through the archive. Click here to return to the archive.

Note: This article is over a year old and information contained in it may no longer be accurate. Please use the contact information in the lower-left corner to verify any information in this article.

'Presidential spouse' is one of many roles for Paton

August 16, 2006

In her book Abandoned New England, Priscilla Paton references Minnesota icon Garrison Keillor, noting how he blends low and high art to "immortalize the mythical Midwest of 'Lake Woebegon,' home of Norwegian bachelor farmers."

|

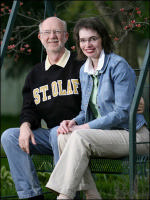

| Priscilla Paton relaxes with her husband, David R. Anderson '74. Paton and Anderson met at Boston College while both were working on advanced degrees in English. |

Now that she and her husband, St. Olaf President David R. Anderson '74, have relocated to Northfield, Paton will continue her exploration of the significance of landscapes as a visiting scholar at Carleton College.

For the past several years, Paton has taught English at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. She and Anderson met while in graduate school at Boston College. Both were pursuing advanced degrees in English and shared an interest in the importance of place in literature.

Paton says she studied and found enjoyment in the high moderns -- authors like Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, T.S. Eliot and F. Scott Fitzgerald -- but it was the poetry of Robert Frost that touched a chord.

"People didn't know what to do with his popularity," Paton says. "He was very well known, but he didn't fit in; he was embarrassing in the academic world."

Despite his mixed reception in academia, Paton says that Frost got her thinking about rural life and how literature is influenced by and connected with place.

Poems such as "Two Look at Two," wherein a couple hiking in the wilderness spot a deer and a buck and all four are frozen in a mutual gaze, depicted a world in which rural life was still dominant.

"In some ways Frost's poetry reflected my background," says Paton, who grew up on a dairy farm in Maine. The writings of Frost and works by other New England poets, such as Elizabeth Bishop, along with a resurgence in environmental consciousness in the 1980s and '90s, inspired Paton and provided a focus for her writing.

She read Amy Clampett, Aldo Leopold, Mary Oliver and Terry Tempest Williams, and discovered not only a dialogue about humans' relationship with the Earth, but also a connection to her own past.

"I found a home in that emerging or rediscovered interest in the environment," Paton says. "It connected my academic interests with my upbringing and bridged what I was reading and what I was thinking."

|

| Abandoned New England |

Abandoned New England (published in 2003 by University Press of New England) is Paton's interdisciplinary analysis of art and words -- from the rugged seascapes of Edward Hopper and Winslow Homer and bleak fields of Andrew Wyeth to the forests, farms and country roads evoked in the writings of Frost and Bishop -- and a union of her affinity for literature and nature.

Paton calls the book an "homage to her childhood," a way of combining "what was with what is now" and reconnecting with history.

"America hasn't learned to see its history the way places like Europe and the Middle East have," Paton says. "Our culture is so obsessed with progress that it hasn't known how to include its own history in the present landscape. We don't know how to include a sense of past visually and culturally."

Paton sees definite similarities between the windswept beaches and New England woods and the farms and forests of rural Minnesota. "The Midwest and the Northeast are both rural places with a traditional farm culture. Minnesota still has vital family farms, which are now an endangered species," Paton says. "Like New England, it's more connected to agriculture and natural resources than most other places."

She also observes a shared nostalgia for the image of "low-key people tied to community" combined with an ambivalent awareness that society has chosen to live differently.

Paton feels this creates an interesting dichotomy, one in which small town or rural life is often idealized, despite the sometimes-grim realities. She references Wyeth's "Christina's World" -- a painting of a solitary girl lying in a desolate field looking toward a dilapidated farmhouse on the horizon -- to illustrate her point. "People love the painting, but they wouldn't want to live there," Paton says.

|

| Howard and the Sitter Surprise |

Recently, Paton's interest in the environment in literature has led to her examining the representation of animals. "As I was reading and writing about landscape, animals kept showing up," she says. "They're part of the environment and have emerged as a topic of interest."

She adds, "At the same time, we're crowding animals more and more. We still don't know how to share space well with them." She cites as an example Ohio's deer infestation and the resulting problems such as the decimation of crops and the debate over hiring hunters to thin the herds.

"Deer were rare when Frost wrote his poem and when [the Walt Disney cartoon] Bambi came out," she says. "The mystical aura around deer in the early-20th century is in part influenced by that rarity."

As with rural landscapes, Paton says that animals in fiction and popular culture are frequently idealized, and these problems of contested space are commonly overlooked. "In movies like Bambi and March of the Penguins animals seem much nicer and easier to relate to than people," she says. "Animals are still very different from us, and we can't turn them into storybook creatures."

Paton still acknowledges that animals have the ability to inspire imagination, and in her acclaimed children's book, Howard and the Sitter Surprise, an animal plays a significant role. Howard and the Sitter Surprise is the story of a willful young boy, Harold, with a penchant for exasperating babysitters. As a final recourse, Harold's mother calls upon Sarah, a large brown bear, to do the job.

Paton, who would like to write another children's book someday, says her book grew from her son's fascination with animals when he was young, as well as a few of her own grueling experiences as a teen-aged babysitter. "I did a lot of babysitting when I was young, and I had some Howards," she says.

Paton wants to continue writing from an academic base, but is "trying to write more generally" on trends with animals and landscapes. "I'm experimenting with academic essays and personal or journal pieces," she says. Paton has a forthcoming essay in Mosaic on the treatment of animals in poetry, and she has been researching the recent proliferation of "doggy daycares" across the country. "I'm getting out of the area of English literature and into trying to understand more generally the source of images in it," says Paton.

That means, naturally, getting back to the landscape.