XML is a markup language, with roots in text

processing. Markup is annotation added to a body of text to

indicate such features as font choice, line breaks, paragraph and

section structure, and inclusion of figures and tables.

See the example of markup for an

illustration.

We will use the term rendition for a body of text

together with description of a desired format. The markup example

(second box above) is an example of a rendition. Software such as

Microsoft Word and Adobe PageMaker also work with renditions

internally.

A presentation is the result of formatting (third box

above). Presentations are intended for human perception. They need

not use visual media, such as paper or an electronic display: for

example, an SGML document might also generate sound through speakers

for the visually impaired.

Word and PageMaker offer a visual interface that shows the

(visual) presentation of the system's document rendition as one creates

the document. These are examples of WYSIWYG systems (What

You See Is What You Get).

The term markup was coined in 1970 by Charles

Goldfarb, the leader of an IBM team that explored the problem of

document content and interchange beginning in the late 1960's. His

team produced GML (Generalized Markup Language) at that time, and

Goldfarb led an ongoing effort to develop the system and concepts

toward SGML (Standard Generalized Markup Language), resulting in the

first ISO standard for SGML in 1986 and the current version of that

standard in 1991.

SGML supports three fundamental goals:

Common data representation. The markup should provide a

universal representation that all systems can use.

Extensibility. It must be possible to define new

markup for new situations in order to represent all forms of information.

Document type rules. Documents of a common type must

adhere to formally verifiable rules for that type.

Few text processing systems adhere to all of these goals. For

example, Microsoft Word is incompatable with other word processors,

which must convert a Word document to their own internal formats.

However, Word is a de facto standard (unofficial, established

through the fact that many users use it) in many organizations,

including St. Olaf. However, different versions of Word offer

different features. A user cannot define his/her own extensions to

Word, and there are no formal rules for document types.

The LaTeX rendition format is frequently used for CS

publications. LaTeX is frequently entered as markup, although WYSIWYG

editors exist. This language has a consistent standard, and is

extensible. LaTeX offers different document types, with presentation

choices governed by those types. However, there is no rule system for

documents of a particular type.

SGML is commonly used in extremely large scale documentation

applications, such as aircraft maintenance information, government

regulation, and power plant documentation. For example, a single

model of a single commercial aircraft might require 4 million

unique pages of documentation that must be revised and republished

quarterly! [Kimber, in Goldfarb] Of course, Boeing or Airbus produce

many such models. As recently as 2000, applications

such as aircraft documentation represented more information than the

entire web.

SGML markup consists of elements indicated by

tags. For example, one element may represent a paragraph,

another a style choice (e.g., emphasized text, perhaps indicated in

this font), and another a graphic image.

Each element has a start tag and an end tag, which allows for nesting

of elements (e.g., a section contains paragraphs; paragraphs contain

regions of emphasized text). The tags

themselves are delimited with angle brackets, now

familiar in HTML. The language was developed over a 20 year period,

and is rich with capabilities including support for hypertext and for

style sheets, which separate rendition decisions from

document content.

SGML has various idiosyncrasies and complexities that support

large-scale use, but

which increase the learning curve and get in the way of ordinary-sized

applications.

Tim Berners-Lee's WWW Consortium developed XML beginning in 1996,

with a standard published in (ca.) 1998, and additional supporting standards

for links (XLink), style sheets (XSL), etc., emerging thereafter.

Jean Paoli of Microsoft and Jon Bosak of Sun Microsystems led the

effort. XML is a subset of SGML, and the accompanying standards are

generally based on corresponding SGML features.

Like SGML and HTML,

markup tags are delimited by angle brackets, and entities are

delimited by ampersands & and semicolons.

Unlike HTML, the XML language achieves all three of the

SGML goals. In particular, XML is fully

extensible---one can define any desired document type---and formal

rules are defined for each document type, against which individual

documents can be checked for validity. SGML's DTD

format provides one way to define document types and describe their

rules; XML Schema constitute an alternate

aproach.

By 1998, it became clear that XML had important applications

beyond text processing. For example, EDI (Electronic Data

Interchange) technology seeks to automate the way large companies buy

and sell from each other. This automation goes beyond the kind of

transaction a consumer has when they buy a book from

amazon.com: for businesses, purchase orders must be

generated and approved, entries must be made in private accounting

systems, etc.; when conducted through the web, one might refer to this

as integrated e-commerce (although it's only called

B2B, Business to Business, in the media).

XML makes it possible to send for documents in one

format between companies, with each organization then transforming

those documents into their own local formats (often also in XML) as

many times as needed, finally making changes in particular (non-XML)

internal systems. The use of XML rather than custom-built

intermediary languages makes this capability available to even small

businesses.

Document structure. Example:

~cs378/xml/Dog.xml,

SD spec for

Dog class.

_____

Balanced tags. Empty elements. _____

Parsing, verification. _____

_____

_____

_____

_____

-

What is a DOM (Document Object Model)?

DOM is a low-level API (Application Programming Interface) which lets

a programmer deal directly with the contents of an XML document.

There is no pre-processing involved with this process. All that is

necessary is the creation of a DOM tree, which is a complete in-memory

representation of the XML document used to create it. After the DOM

is created, there are many methods already written which allow

programmers to efficiently and recursively navigate their way through

a DOM tree, making changes if necessary.

Creating a Document object (DOM tree)

An XML parser or document builder is a code

object for converting an XML

document into a DOM tree (i.e., an object in the class

Document). DOM does not provide a general-purpose

parser object for performing such conversions, because some options for

a parser object can't just be passed as arguments or settings, but

must be incorporated in the construction of that object. Therefore,

DOM provides a factory for constructing custom parser objects.

A DocumentBuilderFactory (in the javax.xml.parsers package)

is a factory API that enables

applications to obtain a parser that produces DOM object trees from

XML documents. A DocumentBuilder defines the API to obtain

Document instances from an XML document. Using this class, a

programmer can obtain a Document from XML. When we say Document, we

mean a DOM tree.

- To create an DocumentBuilderFactory object, simply make

the call

DocumentBuilderFactory dbf =

DocumentBuilderFactory.newInstance();

- A programmer can then specify the way in which the dbf

object parses the XML document. See the Java API for more information

about these options, such as setValidating(true).

- To create a new DocumentBuilder, simply make the call

DocumentBuilder db = dbf.newDocumentBuilder();

- Lastly, to create a DOM tree (or Document object), simply call

DocumentBuilder's parse method, which can take a variety of

input sources. Again, see the Java API for exact specifications.

- So, the final sequence of calls to create a DOM tree is as

follows:

Document document;

DocumentBuilderFactory dbf = DocumentBuilderFactory.newInstance();

dbf.setValidating(true);

.

. (other parse options)

.

DocumentBuilder db = dbf.newDocumentBuilder();

document = db.parse(some input source);

The argument for parse() method of the

DocumentBuilder class can be a File object

or an InputSource object (look this type up in the

org.xml.sax package). For example, if a

String object str holds your XML document

represented as a single string, then

document = db.parse(new InputSource(new StringReader(str)));

creates a DOM tree document from that string str.

Terminology

There are many terms frequently used by programmers when speaking

about XML and DOM trees. In case you aren't familiar with the

terminology, this will be a brief framework of the most commonly used

terms when speaking about XML and DOM.

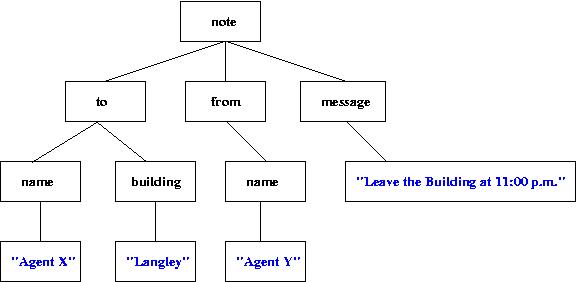

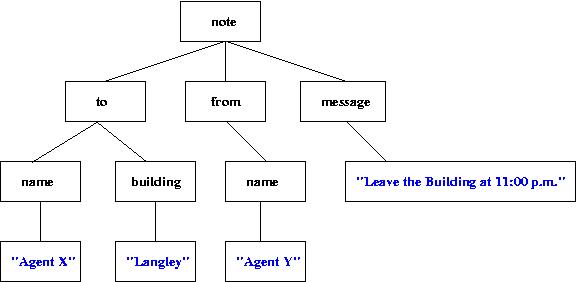

XML Example:

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<!DOCTYPE note SYSTEM "DTD/note.DTD">

<note>

<to>

<name>Agent X</name>

<building>Langley, CIA Headquarters</building>

</to>

<from>

<name>Agent Y</name>

</from>

<message>Leave the building at 11:00 p.m.</message>

</note>

- XML declaration -- Every raw XML document must start with

the first line <?xml version="1.0"?>. This simply

declares the version of XML being used.

- Document Type Declaration -- Every XML document must

contain a line specifying the document type. In this XML document, we

are assuming there is a DTD (Document Type Definition) created located

in the local file system with the path DTD/note.DTD.

- Root Element -- In this XML document, the root element is

the note element. There is only one root element for each XML

document. To obtain the root element of a DOM tree simply call

getDocumentElement(), which returns the root element of a DOM

tree. This is a very helpful method, found in the

org.w3c.dom package.

- Node -- A node is the primary datatype for the entire

Document Object Model. There are 12 node types, which are listed in

the Java API in the Node Interface in the org.w3c.dom package.

Every box in the diagram below is a node.

- Parent -- In this XML document, every node is a parent

node with the exception of the text nodes. Namely, the nodes which

contain "Agent X", "Langley", "Agent Y", and "Leave the Building at

11:00 p.m.".

- Children -- In this XML document, every node is a child

note with the exception of the root element note. Notice

that the content of a node (e.g. "Agent X") is a child. The text

nodes are colored blue in the diagram below. The best way to

interpret parent and child is to draw a diagram of the DOM tree. It

then becomes very clear.

- Document -- The Document interface represents the

entire XML document. When we say Document with a capital D,

that is referring to a DOM tree.

- Well-formed -- An XML document is well-formed if it is

syntactically correct.

- Valid -- An XML document is valid if it conforms to a given

DTD or schema. A document can be well-formed but not valid. However,

a document cannot be valid, but not well-formed.

Visual Tree Representation of a DOM

Useful packages for traversing and modifying a DOM tree

For purposes of simplicity, let's assume that rootElement has

been defined to be the root element of this DOM tree. That is,

rootElement represents the DOM tree specified by the diagram

above. To obtain the value "Agent X", this sequence of calls needs to

be made:

- rootElement.getFirstChild().getFirstChild().getFirstChild()

Try running through this sequence of calls

with the diagram. This is the best way to understand these function

calls. Can you write any other function calls to obtain the value of

the name node? Look at the functions defined in the

org.w3c.dom package in the Java API.

Recursion and DOM trees

An excellent way to gain a strong understanding of the recursion

involved with processing an XML document, it is helpful to spend the

time to write a DOM serializer. A DOM serializer is simply a process

to generate a raw XML document from a DOM tree. So, the number of

children must be known at all times and a recursive process must be

called to deal with any number of children and any number of parents.

Remember that a DOM is really nothing more than a data structure

stored in main memory.

Additionally, like mentioned before, there are 12 types of Nodes,

and each type is displayed differently. Writing a Serializer won't be

an assignment here, but will most likely become a task in the team

project later in the semester. The only way to change the contents of

an XML document is to first parse the document into a DOM tree, then

make changes. However, we would like a new raw XML document to

reflect the changes made to the DOM tree. So, we need to write the

DOM tree to a file to accomplish this. Our project is going to

involve a lot of XML defining the structure of a portfolio, and if the

structure needs to be changed then a DOM tree must be created, changes

made to that DOM tree, and the DOM is rewritten as a file and stored

again. There will be many methods to accomplish this task, and if the

methods are written well the first time, it can be reused for any XML

document.

Example of XML processing in Java

The following example shows recursive modification... (append to

<name>s, add a <department>)

Examples:

~cs378/xml/Contract.dtd,

SpecML.dtd

A Document Type Definition (DTD) is used to constrain the content of

an XML document. For example, if you are trying to model the contents

of a music collection you would like a CD to have only one artist and

one album name. DTDs allow a developer to specify exactly these types

of constraints. A DTD is used to define the legal building blocks of

an XML document. A DTD can be declared inline in your XML document or

as an external document.

- DTD Elements:

<!ELEMENT element-name (element-content)>

- Elements with children (sequences):

<!ELEMENT element-name

(child-element-name, child-element-name, ..., child-element-name)>

- Elements with only character data:

<!ELEMENT element-name (#PCDATA)>

- Elements with one or more elements:

<!ELEMENT element-name (child-element+)>

- Elements with zero or more child elements:

<!ELEMENT element-name (child-element*)>

- Elements with either/or content:

<!ELEMENT element-name

(child-element1|child-element2)>

- There are many other ways to constrain the contents of an XML

document. For a good reference of these options, please visit the

following URL: W3 Schools.

_____